Following Western Texas College’s placement of the Quanah Parker statue on campus, interest in the Comanche culture has grown among the community.

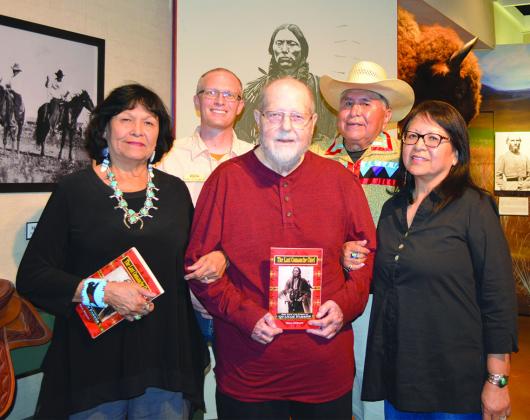

In light of this, the Scurry County Museum asked author Bill Neeley to discuss his book The Last Comanche Chief: The Life and Times of Quanah Parker Thursday night.

“I commend the artwork, and I commend this community for honoring Quanah with this tremendous statue,” Neeley said of the college’s new art piece. “You have a done a good thing by honoring him with your statue.”

Much of Neeley’s life has been dedicated to the study and historical documentation of the Comanches and Parker.

“When we look around here, we can only imagine what it was like before the oil wells and the buildings and all of the modern necessities,” he said. “It was an Indian paradise. Spiritual guidance was important to the Comanches, and I believe the spirit of Quanah is with us right now.”

Neeley’s book outlines the life of Parker from his birth to the moment he knew that Native American freedom had ended. During the presentation, Neeley recounted some of his favorite stories and facts from the book.

“Perhaps Quanah’s greatest achievement of all was saving women and children from Gen. (Ranald Slidell) Mackenzie’s troops,” he said. “Quanah was put in charge of getting the people away from Mackenzie. He fooled Mackenzie’s Tonkawa scouts many times until finally the Tonkawas got on their trail. They were near the caprock, and it was snowing. The Comanches disappeared into the snow, escaping them once again.”

According to Neeley, tensions were high among the Native Americans and United States soldiers at the time.

“There was a lot of hatred, and it’s hard for us to understand how much the soldiers hated the Comanches,” he said. “When Quanah knew that the Comanches would no longer be free, they had a special last dance as free Comanches not far from where we are now.”

It wasn’t until 1924 that Native Americans were finally accepted within the United States.

“Quanah helped establish a church that spanned from Texas to Canada,” Neeley said. “It was the Native American church. They did not grant freedom of religion to Native Americans until 1924 when they were granted full citizenship.”

Through the ups and downs of the Comanche empire’s reign, Neeley has documented the culture’s history for future generations.

“The historian doesn’t judge; the historian lets the people judge,” he said. “I know a medicine woman in Oklahoma, and one time she asked me, ‘Do you know how you were able to write so much about the Comanches?’ She said, ‘The spirit of the old Comanches were guiding your thoughts.’”